Trafficking Risk in Sub-Saharan African Supply Chains

Home / Explore by Commodity / Explore by Country / Understand Risk / Additional Resources / About the Project

Gold

Summary of Key Trafficking in Persons Risk Factors in Gold Production

Long, Complex, and/or Non-transparent Supply Chains

✓ Undesirable and Hazardous Work

✓ Vulnerable Workforce

Child Labor

Migrant Labor

Gendered Dynamics of Production

✓ Associated Contextual Factors Contributing to Trafficking in Persons Vulnerability

Association with Organized Crime/Armed Conflict

Association with State Corruption

Association with Environmental Degradation

Association with Large-scale Land Acquisition/Displacement

Association with Sex Trafficking

Overview of Gold Production in Sub-Saharan Africa

TRADE

Africa currently produces about half of the world’s gold supply.[1]

Ghana is the continent’s largest exporter of gold, recently surpassing South Africa. Burkina Faso, Tanzania, Mali, Zimbabwe, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Uganda, and Senegal round out the top ten sub-Saharan African exporters.[2]

FEATURES OF PRODUCTION AND SUPPLY CHAIN

The majority of the word’s gold – an estimated 75 percent – is produced by large, multinational companies using advanced technology to extract gold in large-scale mines.[4] The rest is produced by artisanal mines, a process referred to as artisanal small-scale mining (ASM).[5]

Generally, artisanal or informal gold mining is a more dangerous and lower-paid occupation than mining in large, formalized mines. This is due to a lack of technology or formalized structures of accountability. When mines operate in protected areas and/or fail to comply with environmental, tax, and labor law, they can be classified as informal mines. These mines operate clandestinely and fail to abide by the law. They generally lack permits, do not pay taxes, lack environmental impact analyses, and have lower employment and labor standards. These mines are not necessarily small, and can operate with international capital, with profits that can run into the billions. Precisely because these mines operate outside of the purview of the state, the amount of gold that they produce often does not factor into international gold production calculations, so their scale may be very significantly underestimated. The workers employed in these mines are generally poorer, more marginalized, and more vulnerable to extreme forms of labor exploitation, including human trafficking.[6]

Labor trafficking is most likely to occur in artisanal and small-scale mining operations, with a particularly heightened risk in illegal mining.

Gold is mined either through hard-rock or alluvial mining. In hard-rock mining, minerals and metals are extracted from rock, which can be done in large open-pit mining or in tunnels that are dug into rock faces. In alluvial mining, minerals and metals are extracted from water. This can be done through panning in rivers; sluicing, in which water is combined with materials (such as sand and dirt) and channeled into boxes that sift and separate the minerals and metals from the material; and dredging, in which minerals and metal-laced sediment are sucked up from sediment in bodies of water.[7]

After the gold is mined, it must be separated from the material that bears it. In hard-rock mining, the rock is often ground into dust. The gold can either be separated using gravity concentration or chemical processes. Both mercury and cyanide are used and these chemicals must then be burnt off.[8] In artisanal and small-scale mining, mercury is used, and this dangerous process may take place in or around miners’ homes.[9]

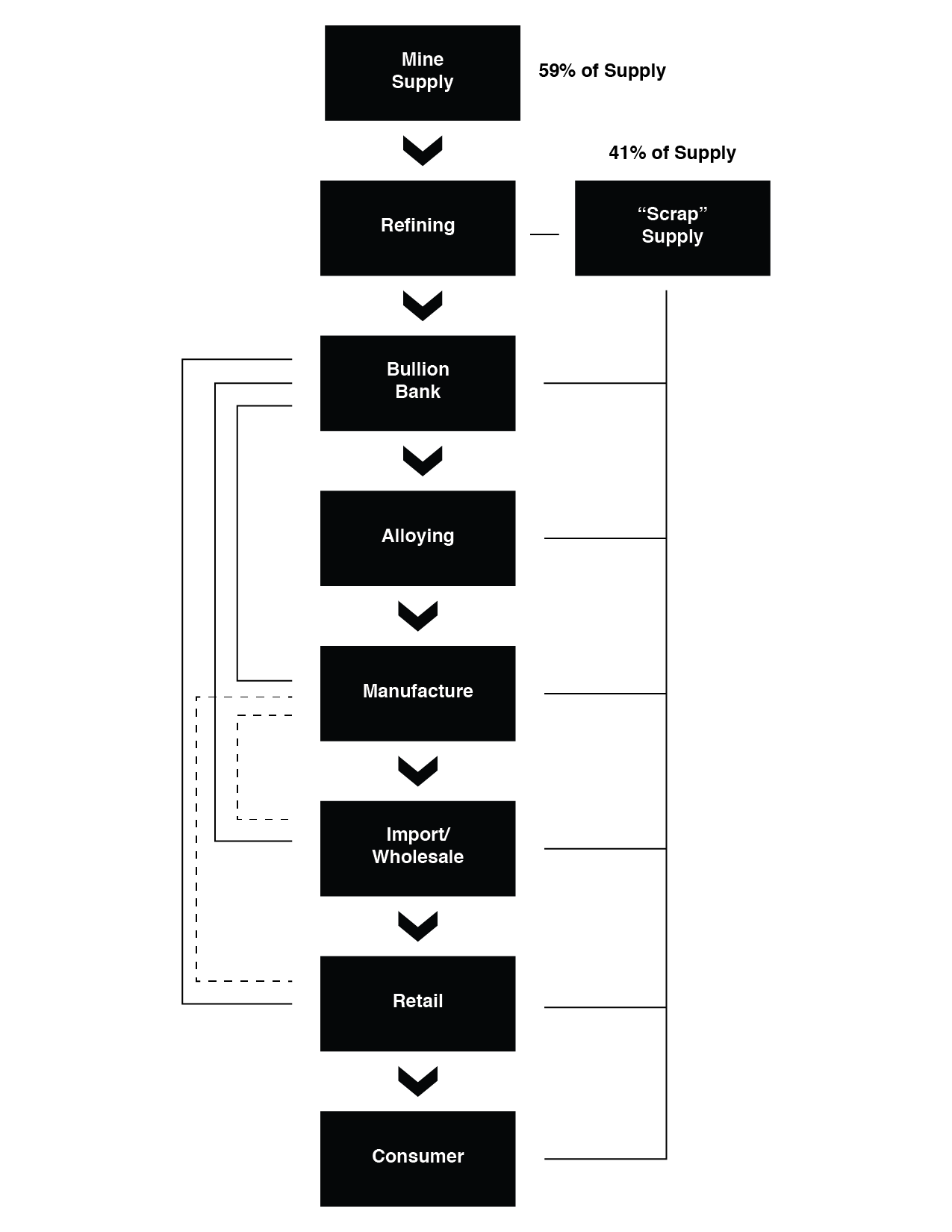

Example of Gold Supply Chain Model

[10]

Africa loses more each year through smuggling and other informal transfers of income than they receive each year in aid and foreign direct investments. The continent loses 38.4 billion USD a year through trade mispricing and another 25 billion USD a year through other illicit cash flows.[12] Gold smuggling plays a large role in this financial loss, although the mechanisms vary by region. In the International Conference of the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR), illicit trading begins when smugglers utilize the weak chain of custody procedures to move gold from the Democratic Republic of the Congo to Uganda, Kenya, Burundi, and Tanzania.[13] Conservative estimates report that 80 percent (over 22 tons) of ASM gold mined in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is smuggled out,[14] other estimates report that the number is as high as 98 percent.[15] In 2011, the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s loss in royalties was 20 million USD.[16]

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) receives a significant portion of gold smuggled from Africa. Ten percent of the UAE’s gold imports come from the ICGRL.[17] There are large discrepancies between reported exports of gold from ICGRL countries and the UAE’s imports of ICGRL gold.[18] The UAE has especially strong ties with the Sudanese gold market. It is estimated that between 2010 and 2014, 105,822 pounds of gold were smuggled into the UAE from Darfur, amounting to a value of USD 123 million.[19] Although exact data is unavailable, it is estimated that the UAE is a top importer of gold smuggled from the Central African Republic and West Africa.[20] From 2011 to 2014 the UAE’s imports of Malian gold surpassed Mali’s total reported production every year.[21]

There are loopholes in Emirati law that enable import of smuggled or illicitly mined gold. The UAE exempts customs declarations of gold that travels into the country in carry-on bags, making it impossible to know where gold is comes from.[22] Importers are not required to provide proof of origin when bringing gold into the UAE.[23] Gold traders then take their product to the gold market in Dubai, bypassing the Dubai Multi-Commodities Centre, an enterprise in charge of regulating the trade of precious minerals in the country.[24]

UAE itself is a top exporter of gold to Switzerland. Once gold reaches refineries in countries including the United States, the UAE, and Switzerland, it becomes even more difficult to identify the origin of the gold. Gold from all over the world may be mixed and processed together. Refineries sell gold to banks, jewelry companies, and electronic producers around the world.[25] After gold is mined and processed, it may be mixed with stronger metals to create an alloy. Processed gold is sold to manufacturers, who produce jewelry and other goods, as well as retailers. Because of the use of scrap gold and the mixing of gold from multiple sources, it is very difficult to track the origin of the gold in specific products.

Key Documented Trafficking in Persons Risk Factors in Gold Production

According to the U.S. Department of State 2019 Trafficking in Persons Report, gold is produced with trafficking or trafficking risk in Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, and Senegal.[26]

According to the 2018 U.S. Department of Labor’s List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, gold is produced with forced labor Burkina Faso and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[27]

UNDESIRABLE AND HAZARDOUS WORK

Gold mining and processing presents serious health hazards to all workers, especially children. The mining shafts, in which workers, including teenage boys, often work are usually unstable, and children can suffer severe injuries and deaths from falls and collapsed mine shafts.[28] The dust from pulverizing stone can lead to lung damage. Younger children often dig out the pits with sharp tools and carry heavy bags of ore, both of which can lead to musculoskeletal injuries.

In informal and illegal mining, powdered ore is mixed with mercury to create an amalgam that workers burn to evaporate the mercury and collect the gold. Women and children often complete this task at mining camps. This process is detrimental to the worker’s health as exposure to mercury can cause developmental and neurological problems, especially among children.[29] Mercury may be ingested (accidentally during work or when it contaminates water), absorbed through the skin (when it is handled with bare hands or miners have to swim in mercury contaminated water), or inhaled (when the mercury is burnt off of pieces of gold). This can result in inflammation of vital organs, the inability to urinate, shock, and death. It can also result in skin lesions, irritation to the lungs, difficulty breathing, and permanent damage to the nervous system.[30]

Hazardous working conditions are particularly tied to mines operating without any government oversight. For example, in Uganda, Global Witness detailed that unlicensed mines lack any government oversight or necessary safety provisions, exposing workers, including children to potential mine shaft collapse and hazardous chemicals.[31]

Lead can also be used in artisanal gold mining, and can impact surrounding communities. In Nigeria, hundreds of children in Zamfara state have died from lead poisoning because of artisanal gold mining activity, and thousands more are suffering from or at risk for lead poisoning.[32] Some of the lead poisoning cases have been from association with miners or due to the proximity of homes to the mines.[33]

VULNERABLE WORKFORCE

Child Labor

According to the 2018 U.S. Department of Labor’s List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, gold is produced with child labor in Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda.[34]

Artisanal gold mining in sub-Saharan Africa is heavily associated with worst forms of child labor. In general, child laborers in gold mining include both children working voluntarily as a means of supporting themselves or their families as well as children who have been trafficked. In the case of child trafficking in West Africa, children from local communities and neighboring countries have been trafficked into informal gold mining. In 2012, Interpol reported rescuing trafficked children from mines in Burkina Faso.[35]

Workers, including child workers, are often required to work long shifts, sometimes working up to 24 hours at a time. Child workers miss out on educational opportunities, as mining requires children to skip or forgo school entirely.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that the Sahel region in West Africa accounts for a quarter of all child labor in mining.[36] The ILO indicates that 70 percent of all children working in the area are less than 15 years old.[37] While the majority of gold in Burkina Faso and Mali is produced by large-scale commercial mines, often owned by foreign companies, small-scale mining offers an opportunity for income in a region ranked among the world’s poorest and least developed. The vast majority of child labor is associated with these small-scale mines. Many children working in mines work alongside their families and live with their families in camps near the mines. In other cases, children, particularly juvenile boys, may migrate by themselves to seek livelihood opportunities. Although much of the reporting has focused on children who migrate willingly, either individually or with their families, police have rescued children who were trafficked to gold mines in Burkina Faso.

Hazardous child labor has been well documented in Ghana, most notably by a 2015 report from Human Rights Watch. According to that report, thousands of children are involved in hazardous gold mining in artisanal gold mines in Ghana. These children may work with their families or independently. They are involved in a range of tasks including excavation in shafts, carrying ore, and crushing ore as well as washing ore with mercury. Children involved in gold mining – in Ghana and elsewhere – experience significant health consequences including bone and joint damage, respiratory disease, and mercury poisoning. Children have also died in mine collapses.[38]

[39]

Discoveries of gold in a region can lead to “rushes,” particularly in areas where people have lost other livelihood options. These rushes can precipitate large scale migrations and the creation of a highly vulnerable population living in isolation in mining camps. In Uganda, there are an estimated 50,000 migrants in mining camps.[40] Undocumented foreign workers – particularly workers laid off from mines in Zimbabwe – have been noted in the illegal mining sector of South Africa.[41] In the Kedougou region of Senegal, villagers who cannot support their families through agriculture or have lost their land to logging have turned to gold mining as a necessity. They are joined by international migrants from the neighboring countries of Mali, Guinea, Gambia, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Togo, and Nigeria.[42]

Gendered Dynamics of Production

Women are typically involved in ore processing, including the use of mercury in artisanal gold mining. Mercury exposure has increased risk for pregnant women as it can harm the developing fetus.[43]

ASSOCIATED CONTEXTUAL FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS VULNERABILITY

Association with Organized Crime/Armed Conflict

The high value and ease with which gold can be smuggled and sold into formal supply chains makes it an attractive form of income for armed groups. Armed groups may use profits from gold mining to fund their operations – which may involve other forms of trafficking such as sex trafficking and child soldiers. In some cases, these groups are perpetrators of trafficking.

Human trafficking in the Democratic Republic of the Congo occurs in North and South Kivu where armed groups control mines, including gold mines. Miners may be forced to work under threat of violence or may be required to pay a “tax” to armed groups. Profits from gold mining, as well as mining of minerals such as cassiterite, columbite-tantalite, and wolframite, have funded the on-going conflict in the country.[44] A study conducted between 2013 and 2015 found that 65 percent of gold mines had an armed presence.[45]

Armed groups in Central African Republic are also funded by control of artisanal mining operations, including gold mines.[46] In some cases, mines previously operated by international companies have been overtaken by rebel groups who then run the mines, demanding “protection payments” from the artisanal miners who work there.[47]

The U.N. has noted that illicit gold mining and smuggling is funding the ongoing conflict in Sudan, [48] which is associated with the use of child soldiers.[49] According to the U.S. Department of State, children have been used as combatants by the Sudanese military and there have been reports that the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Sudanese Rapid Response Forces recruited boys under 18 years old.[50] A U.N. expert council also reported that child combatants took part in tribal clashes for control of gold mines.[51]

In South Africa, after closures of several commercial mines led to the unemployment of over 180,000 miners, illegal gold mining increased significantly.[52] Much of the illegal mining activity is associated with local gangs who control the mines.[53]

Gold from several African countries embroiled in conflict, most notably the Great Lakes Region, is smuggled at high rates.[54] Gold smuggling allows gold mined from sites controlled by armed groups to enter legitimate supply chain. It also encourages illegal gold mining activities in general and decreases government revenues.[55] Uganda, which has refining capability, is thought to be a major regional receiver of gold smuggled from Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[56]

Association with State Corruption

Verité research has noted a strong link between gold mining – particularly illegal gold mining – and corruption in other global regions; this pattern plays out in sub-Saharan Africa as well.[57] Large commercial mining operations have been accused of making bribery payments to government officials.[58] In Uganda, Global Witness details corruption associated with gold mining and exploration licenses granted to large corporations.[59] Illegal mining by foreign miners in Ghana – which sometimes led to eruptions of violence – has been tied to government corruption.[60]

[61]

Gold mining in general is hazardous to the environment as it can contribute to desertification/deforestation in already vulnerable areas, leading to loss of livelihood for local populations. In addition to loss of livelihoods, local populations may lose access to potable water, due to the heavy use of mercury in artisanal gold mining.[62] Large-scale mining operations can also disrupt water sources.[63] Mine shafts in artisanal mining are constructed with trees, which can contribute to deforestation.[64] Dust – produced by crushing ore – and noise pollution are common and can threaten bio-diversity.[65]

Association with Sex Trafficking

Some gold mining operations in sub-Saharan Africa have been associated with sex trafficking and child prostitution. Large mining areas bringing together transitory populations are particularly conducive to sexual exploitation.[66] In Ghana, girls who are as young as 10 are trafficked to mining camps.[67] In Mali, over 12 percent of sex workers in mining towns were between 15 and 19, and a majority were foreign workers from Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire.[68] Child prostitution and child sex trafficking has been noted anecdotally around mining camps in Mali.[69] Porous regional borders allow for regional trafficking to occur.[70] The gold rush in Senegal is increasing demand for sex workers for miners who often believe that paying for sex will increase their chances of finding gold.[71] Women from Nigeria are promised work in Europe and then are left in Kedougou, Senegal’s gold mining region.[72] They are stripped of their documents and often owe traffickers up to 4,900 USD.[73]

In Tanzania, girls around mining sites endure sexual harassment and are often pressured into engaging in sex work. There is also evidence that girls are forced into commercial sexual exploitation in mining areas.[74] In the North Mara mine in Tanzania run by Barrick Gold, a Canadian corporation, women were reportedly coerced into sex with local police officers and security guards at the mines.[75] In Mozambican gold mines, sex workers are brought from Zimbabwe by truck every Thursday because mining is prohibited on Fridays. The high price of gold in the area fuels the demand for sex workers for miners.[76]

Related Resources

Compliance Resources for Companies

Resources for Addressing Industry-Wide Issues and Root Causes

Explore Risk in Global Commodity Supply Chains

American Bar Association ROLI Case Study: Eritrean Mining Industry

Endnotes

[1] Gajigo, Ousman; Mutambatsere, Emelly; Ndiaye, Guirane. African Development Bank Group. Gold Mining in Africa: Maximizing Economic Returns for Countries. March 2012. https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/WPS%20No%20147%20Gold%20Mining%20in%20Africa%20M Production and Global Value Chainaximizing%20Economic%20Returns%20for%20Countries%20120329.pdf.

[2] International Trade Centre. Trade Map. www.trademap.org.

Gajigo, Ousman; Mutambatsere, Emelly; Ndiaye, Guirane. African Development Bank Group. Gold Mining in Africa: Maximizing Economic Returns for Countries. March 2012. https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/WPS%20No%20147%20Gold%20Mining%20in%20Africa.%20M Production and Global Value Chainaximizing%20Economic%20Returns%20for%20Countries%20120329.pdf.

[3] International Trade Centre. Trade Map. www.trademap.org.

[4] Verité. Risk Analysis of Indicators of Forced labor and Human Trafficking in Illegal Gold Mining in Peru. 2013. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/IndicatorsofForcedLaborinGoldMininginPeru.pdf.

Larmer, Brook. “The Real Price of Gold.” National Geographic. January 2009. https://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2009/01/gold/larmer-text.

[5] Larmer, Brook. “The Real Price of Gold.” National Geographic. January 2009. https://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2009/01/gold/larmer-text.

[6] Verité. Risk Analysis of Indicators of Forced labor and Human Trafficking in Illegal Gold Mining in Peru. 2013. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/IndicatorsofForcedLaborinGoldMininginPeru.pdf

Swenson, Jennifer J. et al. Gold Mining in the Peruvian Amazon: Global Prices, Deforestation, and Mercury Imports. April 11, 2011. PLoS ONE 6(4). https://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0018875#pone.0018875-‐Veiga1.

[7] Ethical Gold Fund. Mining Process. https://www.ethicalgoldfund.com/#!mining-process/c248p.

[8] Verité. Risk Analysis of Indicators of Forced labor and Human Trafficking in Illegal Gold Mining in Peru. 2013. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/IndicatorsofForcedLaborinGoldMininginPeru.pdf.

[9] United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP). A Practical Guide: Reducing Mercury Use in Artisanal and Small Scale Gold Mining. July 2012. https://www.unep.org/chemicalsandwaste/Portals/9/Mercury/Documents/ASGM/Techdoc/UNEP%20Tech%20Doc%20APRIL%202012_120608b_web.pdf.

[10] Responsible Jewelry Council. Gold and the Jewelry Supply Chain. May 18, 2010. https://www.responsiblejewellery.com/files/RJC_18_May_Philip_Olden.pdf.

[11] Human Rights Watch (HRW). Mali: Artisanal Mines Produce Gold with Child Labor. December 6, 2011. https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/12/06/mali-artisanal-mines-produce-gold-child-labor.

[12] Gatimu, Sebatstian. Institute for Security Studies. “The True cost of mineral smuggling in the DRC.” January 11, 2016. https://issafrica.org/iss-today/the-true-cost-of-mineral-smuggling-in-the-drc.

[13] Martin, Alan. Taylor, Bernard. Partnership Africa Canada. All that Glitters is Not Gold: Dubai, Congo and the Illicit Trade of Conflict Minerals. May 2014. https://www.africaportal.org/dspace/articles/all-glitters-not-gold-dubai-congo-and-illicit-trade-conflict-minerals.

[14] Blore, Shawn. Partnership Africa Canada. Contraband Gold in the Great Lakes Region: In Region Versus Out-region Smuggling. May 2015. https://www.africaportal.org/dspace/articles/contraband-gold-great-lakes-region-region-cross-border-gold-flows-versus-out-region.

[15] Gatimu, Sebatstian. Institute for Security Studies. “The True cost of mineral smuggling in the DRC.” January 11, 2016. https://issafrica.org/iss-today/the-true-cost-of-mineral-smuggling-in-the-drc.

[16] Blore, Shawn. Partnership Africa Canada. Contraband Gold in the Great Lakes Region: In Region Versus Out-region Smuggling. May 2015. https://www.africaportal.org/dspace/articles/contraband-gold-great-lakes-region-region-cross-border-gold-flows-versus-out-region.

[17] Martin, Alan. Taylor, Bernard. Partnership Africa Canada. All that Glitters is Not Gold: Dubai, Congo and the Illicit Trade of Conflict Minerals. May 2014. https://www.africaportal.org/dspace/articles/all-glitters-not-gold-dubai-congo-and-illicit-trade-conflict-minerals.

[18] Martin, Alan. Taylor, Bernard. Partnership Africa Canada. All that Glitters is Not Gold: Dubai, Congo and the Illicit Trade of Conflict Minerals. May 2014. https://www.africaportal.org/dspace/articles/all-glitters-not-gold-dubai-congo-and-illicit-trade-conflict-minerals.

[19] Charbonneau, Louis. Nichols, Michelle. Reuters. “U.N. experts report cluster bombs, gold smuggling in Darfur.” April 5, 2016. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-sudan-darfur-un-idUSKCN0X22SL.

[20] Matthysen, Ken; Clarkson, Iain. Gold and Diamonds in the Central African Republic. February 2013. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Gold%20and%20diamonds%20in%20the%20Central%20African%20Republic.pdf.

[21] Martin, Alan. Helbig de Balzac, Hélène. Partnership Africa Canada. The West African El Dorado: Mapping the Illicit Trade of Gold in Côte d’Ivoire, Mali and Burkina Faso. January 2017. https://www.africaportal.org/dspace/articles/west-african-el-dorado-mapping-illicit-trade-gold-c%C3%B4te-d%E2%80%99ivoire-mali-and-burkina.

[22] Martin, Alan. Helbig de Balzac, Hélène. Partnership Africa Canada. The West African El Dorado: Mapping the Illicit Trade of Gold in Côte d’Ivoire, Mali and Burkina Faso. January 2017. https://www.africaportal.org/dspace/articles/west-african-el-dorado-mapping-illicit-trade-gold-c%C3%B4te-d%E2%80%99ivoire-mali-and-burkina.

[23] Martin, Alan. Taylor, Bernard. Partnership Africa Canada. All that Glitters is Not Gold: Dubai, Congo and the Illicit Trade of Conflict Minerals. May 2014. https://www.africaportal.org/dspace/articles/all-glitters-not-gold-dubai-congo-and-illicit-trade-conflict-minerals.

[24] Martin, Alan. Helbig de Balzac, Hélène. Partnership Africa Canada. The West African El Dorado: Mapping the Illicit Trade of Gold in Côte d’Ivoire, Mali and Burkina Faso. January 2017. https://www.africaportal.org/dspace/articles/west-african-el-dorado-mapping-illicit-trade-gold-c%C3%B4te-d%E2%80%99ivoire-mali-and-burkina.

[25] Verité. Risk Analysis of Indicators of Forced labor and Human Trafficking in Illegal Gold Mining in Peru. 2013. https://verite.org/sites/default/files/images/IndicatorsofForcedLaborinGoldMininginPeru.pdf.

[26] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2019. https://www.state.gov/reports/2019-trafficking-in-persons-report/.

[27] U.S. Department of Labor. 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. 2018. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ILAB/ListofGoods.pdf .

[28] Internal Verité research.

[29] Human Rights Watch (HRW). Toxic Toil: Child Labor and Mercury Exposure in Tanzania’s Small-Scale Gold Mines.” August 2013. https://www.hrw.org/node/118031/.

[30] International Labor Organization (ILO). Peligros, Riesgos y Daños a La Salud de Los Niños y Niñas que Trabajan en la Minería Artesanal. Organización Internacional del Trabajo. 2005. https://white.oit.org.pe/ipec/documentos/cartilla_riesgos_min.pdf.

[31] Human Rights Watch (HRW). Uganda: Undermined. June 2017. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/oil-gas-and-mining/uganda-undermined/.

[32] Grossman, Elizabeth. Yale Environment 360. “How a Gold Mining Boom is Killing the Children of Nigeria.” March 1, 2012. https://e360.yale.edu/features/how_a_gold_mining_boom_is_killing_the_children_of_nigeria.

[33] Human Rights Watch (HRW). A Heavy Price: Lead Poisoning and Gold Mining in Nigeria’s Zamfara State. 2011. https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/related_material/Nigeria_0212.pdf.

[34] U.S. Department of Labor. 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. 2018. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ILAB/ListofGoods.pdf.

[35] Interpol. Operations. https://www.interpol.int/Crime-areas/Trafficking-in-human-beings/Operations/Forced-child-labour.

[36] International Labor Organization. Child Labour in Gold Mining: The Problem. https://www.ilo.org/ipecinfo/product/download.do?type=document&id=4146.

[37] International Labor Organization. Child Labour in Gold Mining: The Problem. https://www.ilo.org/ipecinfo/product/download.do?type=document&id=4146.

[38] Human Rights Watch (HRW). Precious Metals, Cheap Labor. Child Labor and Corporate Responsibility in Ghana’s Artisanal Gold Mines. 2015. https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/06/10/precious-metal-cheap-labor/child-labor-and-corporate-responsibility-ghanas.

[39] United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF.) Child Protection Data. https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/child-labour/.

[40] Human Rights Watch (HRW). Uganda: Undermined. June 2017. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/oil-gas-and-mining/uganda-undermined/.

[41] CNN. “South Africa’s zama zamas: Is this the world’s worst job?” August 10, 2015. https://www.cnn.com/2015/08/10/africa/south-africa-illegal-mining/index.html.

[42] Thorsen, Dorte. Children Working in Mines and Quarries – Evidence from West and Central Africa. UNICEF. April 2012. https://www.unicef.org/wcaro/english/Briefing_paper_No_4_-_children_working_in_mines_and_quarries.pdf.

[43] World Health Organization. Artisanal and small-scale gold mining and health: Environmental and occupational health hazards associated with artisanal and small-scale gold mining. 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/247195/1/9789241510271-eng.pdf.

[44] Free the Slaves. The Congo Report: Slavery in Conflict Minerals. June 2011. https://www.freetheslaves.net/document.doc?id=243.

Global Witness. Faced With A Gun, What Can You Do?. 2009. https://www.globalwitness.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/englishsummary.pdf.

[45] The Financial Times. “’Conflict gold’ blights the Democratic Republic of Congo.” January 30, 2017. https://blogs.ft.com/beyond-brics/2017/01/30/conflict-gold-blights-the-democratic-republic-of-congo/?mhq5j=e1.

OECD. Mineral Supply Chains Due Diligence. 2015. https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/Mineral-Supply-Chains-DRC-Due-Diligence-Report.pdf.

IPIS Research. Democratic Republic of Congo. https://ipisresearch.be/country/democratic-republic-of-the-congo/.

[46] Flynn, Daniel. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-centralafrica-resources-insight-idUSKBN0FY0MN20140729.

[47] Hoje, Katarina. VOA News. “Rebels Retain Control of Rich Mine in Central African Republic.” May 9, 2014. https://www.voanews.com/a/rebels-retain-control-mine-central-african-republic/2530046.html.

[48] Charbonneau, Louis. Nichols, Michelle. Reuters. “U.N. experts report cluster bombs, gold smuggling in Darfur.” April 5, 2016. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-sudan-darfur-un-idUSKCN0X22SL.

[49] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2016. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/258876.pdf.

[50] U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report. 2016. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/258876.pdf.

[51] United Nations Security Council. “Report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in the Sudan.” March 6, 2017. https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2017/191&Lang=E&Area=UNDOC.

[52] Sieff , Kevin. Independent “South Africa’s illegal gold miners forced to scavenge in abandoned shafts in a perilous attempt to survive.” March 8, 2016 https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/south-africas-illegal-gold-miners-forced-to-scavenge-in-abandoned-shafts-in-a-perilous-attempt-to-a6919561.html.

[53] CNN. “South Africa’s zama zamas: Is this the world’s worst job?” August 10, 2015. https://www.cnn.com/2015/08/10/africa/south-africa-illegal-mining/index.html.

[54] Senelwa, Kennedy. The East African. “UN experts unearth gold smuggling network that funds conflicts in DRC.” July 2, 2016. https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/business/UN-experts-unearth-gold-smuggling-network-in-DR-Congo/2560-3277488-suwp6qz/index.html.

[55] Shoko, Janet. The Africa Report. “Zimbabwe losing millions to gold smuggling.” February 25, 2014. https://www.theafricareport.com/Southern-Africa/zimbabwe-losing-millions-to-gold-smuggling.html.

[56] Human Rights Watch (HRW). Uganda: Undermined. June 2017. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/oil-gas-and-mining/uganda-undermined/.

[57] Verité. The Nexus of Illegal Gold Mining and Human Trafficking in Global Supply Chains: Lessons from Latin America. July 2016. https://verite.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Verite-Report-Illegal_Gold_Mining-2.pdf.

[58] Engler, Yves. Rabble.ca. “Canadian gold mining firm embroiled in labour dispute and corruption allegations in Mauritania.” July 12, 2016. https://rabble.ca/blogs/bloggers/yves-engler/2016/07/canadian-gold-mining-firm-embroiled-labour-dispute-and-corruption.

[59] Human Rights Watch (HRW). Uganda: Undermined. June 2017. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/oil-gas-and-mining/uganda-undermined/.

[60] Crawford, Gordon and Gabriel Botchwey. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics “Conflict, collusion and corruption in small-scale gold mining: Chinese miners and the state in Ghana.” February 9, 2017. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2017.1283479.

[61] Transparency International. 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index. 2019. https://www.transparency.org/cpi2018.

[62] Czech Geological Survey. “Environmental and Health Impacts of Mining in Africa.” 2012. https://www.unesco.org/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/SC/pdf/IGCP594-Proceedings__Windhoek_12-Part1.pdf.

[63] Chimonyo, G.R. and J.V Mupfumi. Centre for Research & Development. “Environmental Impacts Of Gold Mining In Penhalonga.” https://dspace.africaportal.org/jspui/bitstream/123456789/34086/1/environmental%20impacts%20of%20gold%20mining%20in%20penhalonga.pdf?1.

[64] The Guardian. “Battling the Effects of Gold Mining in Burkina Faso.” September 5, 2011. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/gallery/2011/sep/05/burkina-faso-gold-in-pictures#/?picture=378427673&index=10.

[65] Chimonyo, G.R. and J.V Mupfumi. Centre for Research & Development. “Environmental Impacts Of Gold Mining In Penhalonga.” https://dspace.africaportal.org/jspui/bitstream/123456789/34086/1/environmental%20impacts%20of%20gold%20mining%20in%20penhalonga.pdf?1.

Jamasmie, Cecilia. Mining.com. “South Africa has failed to protect locals from gold mine pollution: Harvard report.” October 12, 2016. https://www.mining.com/south-africa-has-failed-to-protect-locals-from-gold-mine-pollution-harvard-report/.

[66] Human Rights Watch (HRW). A Poisonous Mix: Child Labor, Mercury, and Artisanal Gold Mining In Mali. December 6, 2011. https://www.hrw.org/report/2011/12/06/poisonous-mix/child-labor-mercury-and-artisanal-gold-mining-mali.

[67] Gillmore, Christy. Free The Slaves. “New FTS Research Explores Child Slavery in Ghana Gold Mining.” September 4, 2013. https://news.trust.org/item/20170330110114-5j2sz.

[68] Human Rights Watch. A Poisonous Mix: Child Labor, Mercury, and Artisanal Gold Mining In Mali. December 6, 2011. https://www.hrw.org/report/2011/12/06/poisonous-mix/child-labor-mercury-and-artisanal-gold-mining-mali.

[69] Human Rights Watch (HRW). A Poisonous Mix: Child Labor, Mercury, and Artisanal Gold Mining In Mali. December 6, 2011. https://www.hrw.org/report/2011/12/06/poisonous-mix/child-labor-mercury-and-artisanal-gold-mining-mali.

[70] Gillmore, Christy. Free The Slaves. “New FTS Research Explores Child Slavery in Ghana Gold Mining.” September 4, 2013. https://news.trust.org/item/20170330110114-5j2sz.

[71] Gillmore, Christy. Free The Slaves. “New FTS Research Explores Child Slavery in Ghana Gold Mining.” September 4, 2013. https://news.trust.org/item/20170330110114-5j2sz.

[72] Gillmore, Christy. Free The Slaves. “New FTS Research Explores Child Slavery in Ghana Gold Mining.” September 4, 2013. https://news.trust.org/item/20170330110114-5j2sz.

[73] Gillmore, Christy. Free The Slaves. “New FTS Research Explores Child Slavery in Ghana Gold Mining.” September 4, 2013. https://news.trust.org/item/20170330110114-5j2sz.

[74] Human Rights Watch (HRW). “Tanzania: Hazardous Life of Child Gold Miners.” August 28, 2015. https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/08/28/tanzania-hazardous-life-child-gold-miners.

[75] York, Geoffrey. The Globe and Mail. “Claims of sexual abuse in Tanzania blow to Barrick Gold.” May 30, 2011. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/claims-of-sexual-abuses-in-tanzania-blow-to-barrick-gold/article598557/.

[76] Thielke, Thilo. Der Spiegel. “Digging for Survival: The Gold Slaves of Mozambique.” March 24, 2011. https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/digging-for-survival-the-gold-slaves-of-mozambique-a-543047.html.

Trafficking Risk in Sub-Saharan African Supply Chains

Home / Explore by Commodity / Explore by Country / Understand Risk / Additional Resources / About the Project